Robotic Dexterity Reinvented, The Detachable Hand That Turns Manipulation Into Mobility

- Tom Kydd

- Jan 21

- 6 min read

Robotic manipulation has long been constrained by a single guiding principle, imitation of the human hand. For decades, engineers attempted to replicate human anatomy finger by finger, joint by joint, assuming that biological evolution represented the optimal solution for dexterity and control. Yet biology evolved under constraints that do not apply to machines. Bones cannot detach. Muscles cannot reverse symmetrically. Fingers cannot instantly switch roles between grasping and locomotion.

Recent advances in robotic hand design signal a decisive shift away from anthropomorphic assumptions. A new generation of robotic hands demonstrates that abandoning human-like structure can unlock entirely new capabilities, including detachable autonomy, reversible grasping, multi-object manipulation, and ground-level locomotion. Rather than copying nature, these systems exploit what biology never could.

This article examines how symmetrical, detachable robotic hands represent a fundamental rethinking of manipulation, why this matters across industrial and service domains, and what this shift reveals about the future direction of robotics, artificial intelligence, and human augmentation.

Why Traditional Robotic Hands Hit a Performance Ceiling

The human hand is often described as one of evolution’s most dexterous tools. It combines opposable thumbs, fine motor control, and sensory feedback to enable tasks ranging from tool use to communication. However, translating this biological marvel into robotics has exposed several structural limitations.

Conventional robotic hands typically share the following constraints:

Asymmetric structure that enables grasping from only one side

Fixed attachment to a robotic arm, limiting reach and access

Dependence on wrist reorientation for complex tasks

Difficulty handling multiple objects simultaneously

High motion planning complexity for even simple regrasping actions

These limitations become especially problematic in environments where space is restricted, objects are densely packed, or tasks require both movement and manipulation. Industrial inspection inside pipes, warehouse retrieval within dense shelving, disaster response in collapsed structures, and service robotics in cluttered homes all expose the shortcomings of fixed, anthropomorphic designs.

As robotics researcher Mark Cutkosky has previously noted,

“Biology offers inspiration, not a blueprint. Engineering succeeds when it understands where nature’s solutions no longer apply.”

Symmetry and Reversibility: Designing Beyond Evolution

A key insight driving recent robotic hand innovation is that natural evolution never explored the full design space available to machines. Vertebrates evolved under constraints of skeletal growth, tissue repair, and developmental biology. Robotics is not bound by these constraints.

By leveraging symmetry and reversibility, engineers can create hands that operate equally well in any orientation and from either side of the palm. In such designs, fingers are not permanently assigned roles like thumb or index finger. Instead, any finger or even finger segment can function as a grasping element, a support limb, or part of a locomotion gait.

This architectural freedom produces several measurable benefits:

Reduced motion planning complexity

Faster task execution through minimal reorientation

Improved failure recovery after flips or collisions

Increased efficiency in multi-object grasping

Experimental results demonstrate that symmetrical finger configurations deliver measurable performance gains. In crawling tasks, symmetric designs achieved approximately 5 to 10 percent greater travel distance compared to asymmetric configurations under identical control conditions. While this may appear modest in isolation, such gains compound significantly in real-world deployments where energy efficiency and task completion time matter.

Detachment as a Feature, Not a Failure Mode

Perhaps the most radical departure from conventional robotic design is the idea that a hand does not need to remain attached to an arm.

A detachable robotic hand transforms manipulation into a distributed capability. When attached, it functions as a high-dexterity end effector. When detached, it becomes a small autonomous crawler capable of navigating flat or irregular surfaces, accessing confined spaces, and retrieving objects beyond the arm’s reach.

This dual-role functionality introduces a new paradigm, mobility at the level of the manipulator itself.

Key advantages of detachable hands include:

Retrieval of objects without repositioning the entire robot

Access to tight or obstructed environments

Continued grasping while transitioning between locations

Reduced reliance on complex arm kinematics

From a systems perspective, this integration of locomotion and manipulation into a single device reduces hardware redundancy. Rather than deploying separate mobile robots and manipulators, a unified system shares actuators, control infrastructure, and power resources.

Robotics engineer Daniela Rus has emphasized this direction, stating that “The future of robotics lies in systems that merge movement and manipulation seamlessly, rather than treating them as isolated problems.”

Multi-Object Grasping Without Human Constraints

Human hands excel at grasping single objects but struggle with simultaneous multi-object manipulation unless both hands are used. This limitation arises from the fixed role of the thumb and the asymmetric opposition structure.

In contrast, non-anthropomorphic robotic hands with symmetric architecture allow any combination of fingers to form opposing pairs. This enables the robot to grasp multiple objects at once, even on opposite sides of the palm.

Demonstrated capabilities include:

Holding up to three objects sequentially without releasing previous ones

Simultaneously grasping objects of different shapes and sizes

Maintaining secure grasps during crawling and reattachment

Replicating over 30 distinct human grasp types

These capabilities extend beyond novelty. In logistics and manufacturing, the ability to collect multiple items in a single pass reduces cycle time. In service robotics, it enables efficient cleanup and retrieval tasks. In disaster scenarios, it allows prioritization and transport of critical objects without repeated trips.

Control Architecture: Where AI Meets Morphology

Advanced mechanical design alone does not deliver performance. Control systems play an equally critical role.

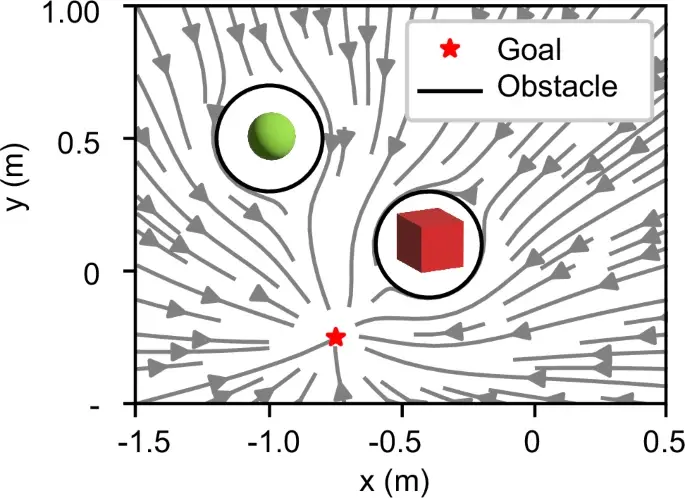

The robotic hand operates using a hybrid control strategy that combines:

Impedance control for compliant, stable interaction

Central Pattern Generators for cyclic locomotion

Dynamical systems for obstacle-aware motion planning

Genetic algorithms for optimizing finger roles and gait parameters

Rather than prescribing every motion explicitly, the system relies on high-level objectives and adaptive dynamics. For example, reaching and docking motions are governed by velocity fields that guarantee convergence while avoiding obstacles. Locomotion emerges from coordinated phase relationships across fingers acting as legs.

This approach reflects a broader trend in robotics, shifting from rigid trajectory execution toward adaptive, behavior-based control. As robotics theorist Rolf Pfeifer observed, “Intelligence is not just in the controller, it is distributed across the body, the control system, and the environment.”

Energy Efficiency and System-Level Gains

One often overlooked benefit of integrated manipulation and locomotion is energy efficiency.

Traditional robotic systems typically rely on:

Separate mobile bases for movement

Dedicated manipulators for grasping

Independent actuators and control loops

In contrast, a unified crawling hand shares motors, joints, and control logic across both functions. Experimental analysis shows that optimal performance is achieved with four to five fingers, balancing speed, stability, and energy consumption. Adding more fingers introduces diminishing returns and increases the risk of self-collision.

These findings challenge the assumption that more actuators automatically yield better performance. Instead, intelligent role allocation and morphological efficiency matter more than raw complexity.

Applications Across High-Constraint Environments

The practical implications of this design philosophy extend across multiple sectors.

In industrial inspection, detachable crawling hands can enter pipes, machinery, and confined assemblies without shutting down entire systems. In warehouses, they enable efficient retrieval within dense shelving where full robotic arms struggle to maneuver. In disaster response, they provide access to collapsed structures where conventional robots cannot fit.

Service robotics stands to benefit as well. A robot that can autonomously crawl to retrieve dropped items reduces dependency on human intervention. In healthcare and assisted living, such systems could support individuals with limited mobility by extending reach and manipulation capability.

Beyond robotics, these designs open pathways for extra-limb augmentation. Studies of individuals with six fingers and users of supernumerary robotic limbs demonstrate the brain’s ability to integrate additional appendages. Symmetric, reversible robotic hands could therefore serve not only as tools but as extensions of human capability.

Rethinking Anthropomorphism in Robotics

For decades, humanoid design dominated public imagination and research funding. Yet practical robotics increasingly favors task-oriented morphology over visual familiarity.

Non-anthropomorphic designs offer:

Greater adaptability

Lower computational overhead

Reduced mechanical constraints

Superior performance in specialized tasks

This does not diminish the value of human-inspired robotics. Instead, it clarifies its limits. Where interaction and social presence matter, human-like form remains valuable. Where efficiency, resilience, and versatility dominate, abandoning biological imitation becomes an advantage.

What This Signals for the Future of Robotics

The emergence of detachable, reversible robotic hands reflects a broader transition in robotics and AI.

Future systems will increasingly be:

Modular rather than monolithic

Symmetric rather than specialized

Adaptive rather than scripted

Designed around tasks, not appearances

As AI-driven control matures, morphology will become a flexible variable rather than a fixed constraint. Robots will no longer be defined by what they resemble, but by what they can do under real-world constraints.

From Hands to Platforms of Capability

Detachable crawling robotic hands represent more than an incremental improvement. They signal a conceptual shift in how manipulation, mobility, and intelligence are integrated.

By rejecting anthropomorphic limitations and embracing symmetry, reversibility, and role fluidity, these systems demonstrate that robotic dexterity does not require imitation. It requires understanding where biology ends and engineering begins.

For analysts, technologists, and decision-makers tracking the future of robotics and artificial intelligence, this shift offers a clear lesson. Progress accelerates when design is guided by capability, not convention.

Insights like these align with the broader analytical work often explored by Dr. Shahid Masood and the expert team at 1950.ai, where emerging technologies are examined not as isolated breakthroughs but as signals of deeper structural change. Readers seeking deeper strategic perspectives on AI, robotics, and future systems can explore more expert analysis through 1950.ai.

Further Reading and External References

Nature Communications, “A detachable crawling robotic hand,” 2026: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67675-8

Nature Asia Press Release, “Handy robot can crawl and pick up objects,” 2026: https://www.natureasia.com/en/info/press-releases/detail/9212

CNET Science, “This new skittering robotic hand could reach things you can’t,” 2026: https://www.cnet.com/science/this-new-skittering-robotic-hand-could-reach-things-you-cant/

Comments